In 1947, during the tenure of the first director, Andrea Corsini (1875-1961), the Florentine collector Carlo Tantini donated to the Institute and Museum of the History of Science a collection of velocipeds and cycles produced between the mid-19th century and the early 20th century. In the 1960s this collection, consisting of about a dozen exemplars, was on display in the technology section of the museum in the basement of the Palazzo Castellani, an area that was completely submerged by the flood. The basement remained inaccessible for several days, but when the waters had subsided and the bicycles re-emerged, it was found that – being made of iron and rubber – they only required a thorough washing to be fit for display again. They can be seen at present in the Museo dell'Arte della Lana in the Tuscan town of Stia. Instead the period posters that decorated the walls of the basement still bear traces of their long immersion in the floodwaters.

The exhibit of cycles and bicycles in the basement, 1962-1966

Vedi tutto

An antique bicycle on display in the basement, 1962-1966

Vedi tutto

Cleaning the Museum's bicycle collection on the sidewalk in front of the Palazzo Castellani

Vedi tutto

Remains of bicycles, early 20th century

Vedi tutto

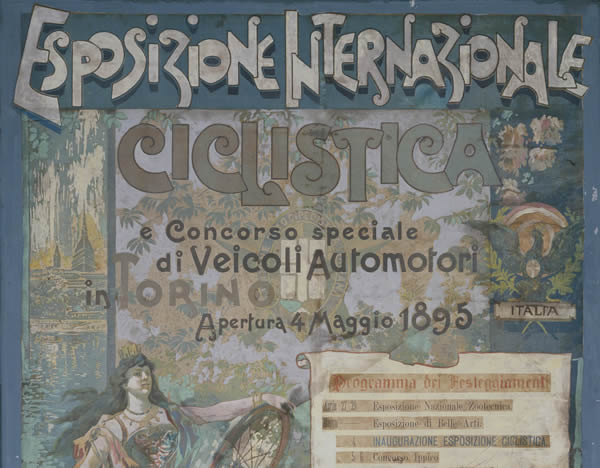

Luigi Giani & Figlio, Esposizione Internazionale Ciclistica, Turin, ca. 1895

Vedi tutto

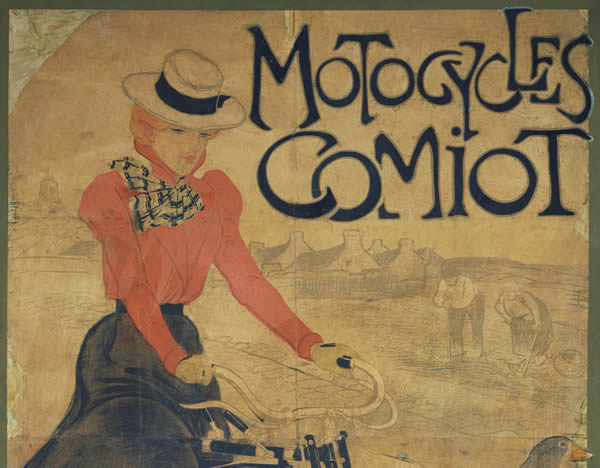

Steinlerg, Motocycles Comiot, Paris, ca. 1900

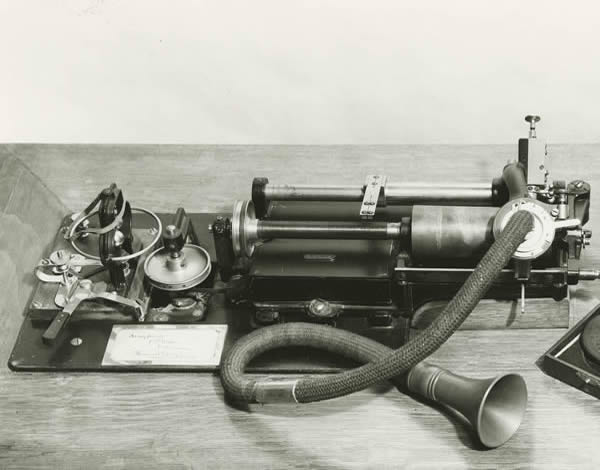

Vedi tuttoOne room on the ground floor of the Museum was dedicated to acoustic devices, including gramophones, phonographs, telephones, and other curiosities. In the only known photograph showing the room as it looked before the flood (see left top image), two exhibits stand out – a "stentorophonic instrument" for use at sea, which originally belonged to the Medici collection (on the left), and an exemplar of Edison's phonograph (in the middle of the room). This room was inundated by the flood and the items that were not lost required extensive restoration. The phonograph had been given by Thomas Alva Edison (1847-1931) as a gift "To my friend E. Fabbri" who was the Florentine Egisto Paolo Fabbri (1828-1894). In 1933 one of his heirs donated the apparatus to the Museo di Storia della Scienza (today Museo Galileo). Count Gaetano Manzoni restored the instrument, which was placed on display again in May 1967.

The room dedicated to acoustic devices, ca. 1964

Vedi tutto

Edison's phonograph with its accessories

Vedi tutto

Thomas A. Edison, Phonograph, 1890 ca.

Vedi tutto

Anonymous, Stentorophonic instrument or Sea horn, Mid-17th century

Vedi tutto

Kellogg Switchboard & Supply Co., Chicago, Wall telephone, 1910 ca.

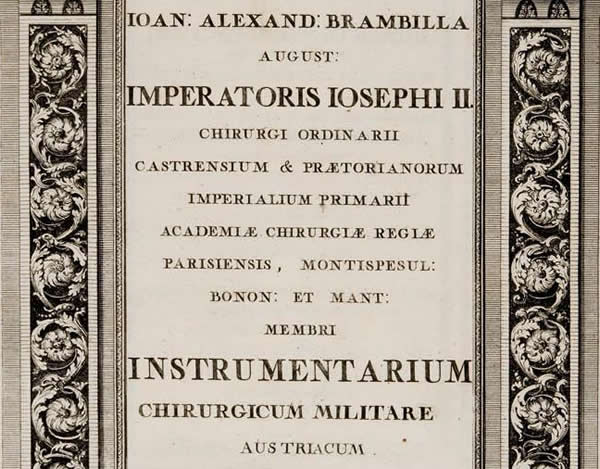

Vedi tuttoOn display in one of the rooms on the ground floor dedicated to medicine were thirty cases of surgical instruments prepared according to the criteria laid out in Instrumentarium chirurgicum, the vade mecum for surgeons by Giovanni Alessandro Brambilla (1728-1800) published in Vienna in 1782. Brambilla was an Italian physician who became the personal surgeon to Emperor Joseph II and played a key role in modernizing the study of surgery in Vienna. These cases were acquired by Peter Leopold of Lorraine for the medical school of the Arcispedale di Santa Maria Nuova. At the time of the flood a copy of Instrumentarium was on display together with the surgical cases and was subjected to irreparable water damage. To help the Museum restore the surgical cases, whose contents were damaged and dispersed, the Institut für Geschichte der Medizin of the University of Vienna, heir to the medical school founded by Brambilla, donated a copy of the volume to the Museum. This made it possible to restore the cases and place them on exhibit again complete with their instruments.

The room of medical exhibits dedicated to Brambilla, 1966

Vedi tutto

The director, Maria Luisa Righini Bonelli, in the flooded room

Vedi tutto

Exhibit of Brambilla's surgical instruments after restoration, 1976

Vedi tutto

Giovanni Alessandro Brambilla, Instrumentarium chirurgicum militare Austriacum, Vienna, litteris Schmidtianis, 1782

Vedi tutto

Joseph Malliard, Surgical case, second half of the 18th century

Vedi tuttoTogether with Brambilla's surgical cases, the Institute and Museum of the History of Science received from the Arcispedale di Santa Maria Nuova 21 anatomical waxworks and 39 plaster models, that had been used to teach obstetrics at the hospital's medical school. These models were on display in a room on the ground floor, together with three teatrini or trionfi – miniature scenes illustrating the themes of human vanity, the transience of life, and the Black Death – which were made by the abbot Gaetano Giulio Zumbo (1656-1701), a wax modeler from Sicily in the service of Cosimo III de' Medici. The anatomical models had been arranged on tables or hung from the walls, and were severely damaged by the flood. Their restoration was carried out by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, whose specialized staff also devised a plan for the handling and conservation of these delicate exhibits. Zumbo's trionfi were repaired as well and are now on display in the zoology section of the Museum of Natural History of Florence, also known as La Specola.

Room containing the exhibit of anatomical models in wax and plaster, 1966, before the flood. In the background, the three teatrini by Gaetano Zumbo

Vedi tutto

The room in the immediate aftermath of the flood

Vedi tutto

Wax models of fetuses, jumbled together with other flood-damaged exhibits

Vedi tutto

The anatomical collection after preliminary cleaning

Vedi tutto

Giuseppe Ferrini and/or Clemente Susini (attr.), Anatomical wax model, Florence, ca. 1775

Vedi tutto

Anonymous, Anatomical clay model, Florence, ca. 1775

Vedi tuttoBefore the flood, chemical and pharmaceutical instruments from the Lorraine collection were on exhibit in two rooms on the ground floor (now occupied by the bookshop and a display of tower clocks). The most important exhibit in this section was the chemistry cabinet of Grand Duke Peter Leopold (1747-1792), equipped with a set of burners, ovens, alembics, glass bottles, and flasks, some of them with their 18th-century contents intact. The waters of the Arno invaded the room, destroying or seriously damaging the fragile equipment, much of it made of glass or fireclay. The chemistry cabinet has been completely restored and can be seen today in Room X, which is dedicated to the Lorraine collections. Unmistakable signs of the flood can be seen in the breaks of many retorts, and in the mud that is mixed with the contents of some of the bottles.

Peter Leopold's chemistry cabinet, as it appeared in ca. 1954

Vedi tutto

The room of alchemy exhibits, ca. 1964

Vedi tutto

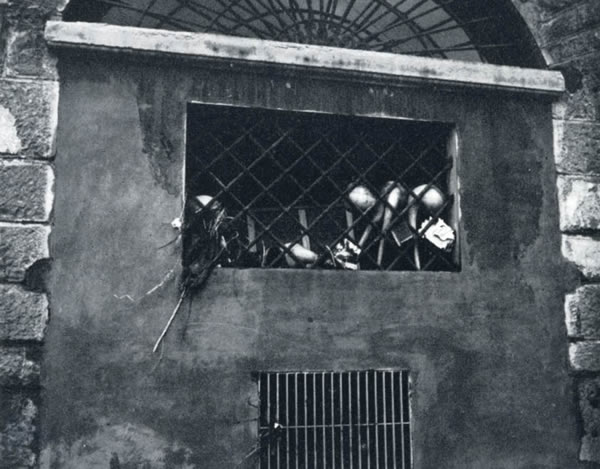

Retorts caught in the metal grill of a window, after the receding of the floodwaters

Vedi tutto

Leo Rossi, Firenze quattro anni dopo, "Epoca", 17 January 1971

Vedi tutto

Bottles containing chemicals, from Grand Duke Peter Leopold's laboratory, second half of the 18th century

Vedi tutto

Josiah Wedgwood, Retorts, second half of the 18th century

Vedi tuttoThe violence of the flood overturned exhibits, destroyed furniture and hangings, and scattered objects helter-skelter. After the waters receded, the urgent task of rescuing items that were buried deep in the mud led to further inadvertent damage. Many objects or parts of them may have been mistaken for rubbish and thrown away. Among the objects that were lost was the splendid decorated case of a clock made by Johann Philipp Treffler (1625-1698) that was on display in the basement as part of the collection of timepieces (now arranged in Room V). Another lost item was a telephone originally belonging to Queen Margherita of Savoy which sat on a shelf in the room of acoustic devices on the ground floor, but was never recovered after the flood.

The clock by Treffler originally on display in the basement

Vedi tutto

Treffler's clock in its original case

Vedi tutto

Queen Margherita of Savoy's telephone in an old photograph

Vedi tutto